citation

Nadia Latif,

"Space, Power and Identity in a Palestinian Refugee Camp ",

REVUE Asylon(s),

N°5, septembre 2008

ISBN : 979-10-95908-09-8 9791095908098, Palestiniens en / hors camps.,

url de référence: http://www.reseau-terra.eu/article800.html

résumé

What then constitutes a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon as a refugee camp ? How have the Palestinian refugees inhabited and experienced these spaces over the years ? This essay examines these questions in the context of Bourj el-Barajneh refugee camp located in the southern suburbs of Beirut. It draws on material collected through participant observation and unstructured interviews during two years of fieldwork (2003-2004, and 2005-2006), as well as research at the archives of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in Geneva (February 2007).

Mots clefs

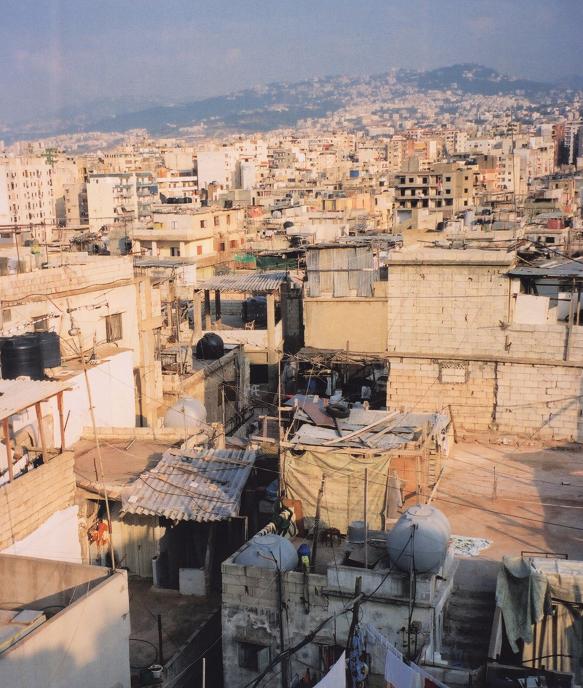

Within social science scholarship, refugee camps are often perceived as sites of incarceration, or as transient spaces providing temporary shelter until their occupants’ return ‘home’, or assimilation into the new ‘home’ provided by a host country (Diken and Laustsen 2005, Perera 2002). However, the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon are among the world’s longest existing refugee camps. Some were originally established at the beginning of the twentieth century to accommodate the survivors of the Armenian massacres in Turkey. Others such as Bourj el-Barajneh were set up in 1948 to accommodate peasant and low-income, urban Palestinian refugees who lacked the means to support themselves. In either case, the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon have now been in existence for almost sixty years and are inhabited by four generations of refugees of whom all but the first know Palestine only from textbooks, the memories of their elders and more recently the globalised media. To a visitor, these camps present the appearance of typical low income settlements—cinderblock housing, overcrowding, unplanned construction, and irregular provision of basic services. In fact recent studies on urbanisation and urban development in Lebanon have categorised them as slums (Fawaz and Peillen 2003). If the manner and type of settlement does not constitute the camps as camps, neither does their demographic makeup per se. Almost every camp has a non-Palestinian population comprised mostly, but not entirely, of Lebanese and Syrian nationals who choose to live there because of low cost of living. Additionally, not all Palestinian refugee residential conglomerations are camps. What then constitutes a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon as a refugee camp ? How have the Palestinian refugees inhabited and experienced these spaces over the years ? This essay examines these questions in the context of Bourj el-Barajneh refugee camp located in the southern suburbs of Beirut. It draws on material collected through participant observation and unstructured interviews during two years of fieldwork (2003-2004, and 2005-2006), as well as research at the archives of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in Geneva (February 2007).

(Bourj el-Barajneh camp today. Courtesy of the MAP UK website [1].)

A Foucaldian approach has often been applied to the study of refugees and refugee camps within social science literature. Anthropologist Liisa Malkki has argued that nationalism’s fiction of an unproblematic link between territory and identity leads to the construction of refugees as “aberrations of the nation-state in need of therapeutic intervention.” The refugee camp then functions as a “‘technology of care and control’….a technology of power entailing the management of space and movement—for peoples out of place” (Malkki 1996 : 444). Similarly, in her work on camps in Kenya, Jennifer Hyndman observes parallels between the strategies employed by colonial administrators to police and control their subject population and the ways in which the spatial layout of refugee camps and humanitarian efforts facilitate the surveillance and control of refugees.

The production of maps, statistics, and assessments by professionals at UNHCR is, I believe, performed with the welfare of the refugees in mind. Nonetheless, their production often occurs without reference to the historical configurations of power that preceded them. In the context of refugee camps, cartography, counting and recording are all acts of management, if not surveillance. They enact controversial power relations between refugees and humanitarian agencies (Hyndman 2000 : 121).

This use of Foucault draws on his insight into the ways in which the production of knowledge is intimately bound to the working of power, in particular his work in Discipline and Punish in which he outlines the discursive and technological development of the prison as the hegemonic strategy of punishment/re-education in modern society (Foucault 1995). By observing contiguity between humanitarian efforts to care for/manage refugee populations and strategies used by colonial and modern states to care for/manage/control and police their citizens, these scholars seek to extend Foucault’s work into spheres he did not explicitly addressed.

Hyndman describes the way the refugee shelters in the camps she worked in were ordered along neat grids. Aerial photographs were used to count them in order to estimate the size of the population. The hierarchy of power relations was mapped onto the spatial organization of the camp in the form of distinct and segregated living spaces for the refugees and the humanitarian organisations’ personnel. The boundaries of the latter were conspicuously marked by two security fences and the deployment of armed guards at night. They also provided their residents with a much higher standard of living conditions in the form of permanent, weather-proof structures, considerably larger person to space ratio, electricity, running water and indoor toilets. In addition, the location of the organisations’ offices, food rations, medical services provision, and police protection was based on ensuring the security of the organisations’ personnel, rather than convenient access for the refugees (Hyndman 2000). None of the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon correspond this spatial order. This is not to say that the camps are not disciplinary spaces in the Foucauldian sense or that power does not mark their spatial and social organisation. On the contrary, the shifts in Bourj el-Barajneh camp’s boundaries and the difference in their permeability over time demonstrate the ways in which power relations are spatially embedded.

Under Lebanese state policy, only those camps that were established through the League of Red Cross Societies (LRCS) and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) with the authorisation of the Lebanese state during 1948-1955 are considered ‘official’ camps and receive UNRWA services (schooling, medical care, sanitation). Residential conglomerations that grew independently of these organisations and without state authorisation as offshoots of ‘official’ camps due to population increase, such as Sabra (an offshoot of Shatila camp), or as a consequence of displacement during the Lebanese civil war (1975-1991), such as Gaza Hospital (located near Shatila camp) are referred to as “gatherings”. Their ‘unofficial’ status bars them from UNRWA service provision, in addition to which they remain largely neglected by most local and Palestinian NGOs. Consequently, living conditions are much worse than in the ‘official’ camps.

Though Bourj el-Barajneh’s site was not selected for the refugees by the Lebanese state or a humanitarian organisation, its location was fairly isolated as is the case with many refugee camps around the world. However, in this case the social economics of ‘charity’ rather than a humanitarian organisation or state’s decision were the determining force. The land allocated to the refugees who settled the camp was located in an undeveloped, sparsely inhabited, agricultural area south of Beirut. Most of the first generation Palestinian refugee inhabitants of Bourj el-Barajneh I interviewed did not know how the camp was established. The usual response to my query was that it had already been there when they arrived. UNRWA promotional material merely states that the camp was set up in 1948 by the LRCS [2]. Research at the IFRC archives in Geneva confirmed that the camp came into existence in 1949 [3] but did not yield any further information. An article by a French researcher claims that a prominent family. the Aghas, from a village in the Galilee called Tarshiha, secured land from the mukhtar of Bourj el-Barajneh village to accommodate less affluent families of their village with whom they had patron-client relations (Gorokhoff 1984). According to this version the Aghas were vacationing in Lebanon when Tarshiha fell to the Haganeh in October 1948 ; so they went to stay with friends in Bourj el-Barajneh, at this time a small village on the southern outskirts of Beirut. Many families from Tarshiha had fled to the southern city of Tyre, and the Lebanese government was planning to transfer them to Aleppo in northern Syria. However, when they heard that the Aghas were already in Beirut, many refused to leave and went up to Bourj el-Barajneh to join them. The Aghas then secured land from the mukhtar for their use in an area south of the current location of the camp, known as Ein el-Sikke. As more and more families from Tarshiha and its neighbouring villages came to join those in Ein el-Sikkeh, more land was needed. A local notable, Haj Rachid, agreed to exchange it with 0.1 sq. km. of his own land for the Palestinians to use as long as they needed it. An interview with a member of another prominent Tarshiha family, the Mustafas, provided a slightly different account. He claimed that his uncle was responsible for securing the land that came to be the camp. His uncle had been an influential person in Tarshiha and had made use of his economic ties with a prominent family from Bourj el-Barajneh to obtain land for the refugees from his village to stay on until they could return. Soon after, when the owner of the land attempted to displace the refugees from his property, they were able to enlist the support of a sympathetic Lebanese general.

Though Gorokhoff’s version and that of my interviewee differ on a number of details, both suggest that the camp came into existence at the initiative of a prominent family from Tarshiha, independently of the LRCS through ties of friendship and patronage between that family and notable Lebanese families. My interviewee’s account also reveals the role these ties played in shaping the settlement and growth of the camp, highlighting their socio-political importance in Lebanese and Palestinian society at that time [4]. They also point to the fact that both parties viewed it as a temporary arrangement until it became possible for the refugees to return to their homes.

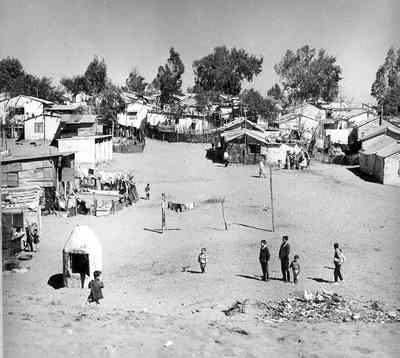

First generation accounts of the camp’s early years make frequent reference to the ever present sand that would get into everything—food, water, bedding, and even clothing.

Some time we had to throw away the dough because the sand got into it, because it would fly around whenever there was a breeze. When we had to fill water it was very hard to walk because the sand was so hot. It would burn our feet. If you had to walk uphill it was really difficult because the sand would sink down. There weren’t any people living here...also there wasn’t an airport, so when they built the airport the area became important. But before it was deserted…There were pine groves and thieves used to hide in them. That where they put us. It was very difficult to live here with the hot sand and the sun. We used to go to the tile factory to bring tiles to put on the sand so we could walk on it…People worked hard in those days. It’s not like that now. Life is easy now.

(Interview with a first generation refugee from Kabri. Bourj el-Barajneh camp, Beirut. March 17, 2006).

Imm K’s bitter pronouncement “That’s where they put us,” highlights the great material hardships of those years of life in tents with a complete dependence on the charity of others for the fulfilment of basic needs such as food, water and shelter. Life is ‘easy’ now in comparison with those terrible years because houses have been built, alleys paved, and water does not have to be brought back from a communal tap located far one’s tent, carried on the head in a metal can under the hot sun of the summer and the damp cold of the winter. Imm K’s statement also appears to support the claim that the camp was established by the inhabitants of Tashiha, since inhabitants of other villages came later perhaps after the camp had been officially recognised by the LRCS (and the through them the Lebanese state). In those days of chaos and upheaval who established the camp and how may have appeared irrelevant details to the refugees whose primary concern was reuniting with their kin and neighbours in a safe place where they could be assured of some sort of support. This would explain why few of the first generation refugees I interviewed knew details of how the camp was established.

Tents and communal bathrooms predominate in memories of those years, as in addition to material impoverishment they embody the lack of privacy and forced intimacy between strangers (particularly in relation to maintaining gender boundaries), that heightened the refugees’ sense of helplessness in the face of social upheaval. And yet not all memories of those days are unhappy :

Imm Z : In the beginning it was safe for our kids to go out to play. When they’d come home from school they used to go outside to play because they weren’t any cars or streets. They used to go to the pine groves. There wasn’t any ‘Amleyeh [5]. There were pine trees in all that area. So when we would finish our cooking and cleaning we used to go there and take our kids with us…They used to make swings. We had fun. There was fresh air and the children were safe…

(Interview with first generation refugee from Qwikat. Bourj el-Barajneh camp, Beirut. April 25, 2006).

Imm Z’s recollection is in reference to the current lack of open spaces in the camp. A consequence of high population density (approximately 20,000 people live in 0.1 sq. km [6].), this has become a big problem. The narrow, cramped alleys are the only places children can play in outdoors. Since most houses are small, poorly lit and ventilated, the alleys do not provide much relief. Neighbours complain about the noise and conscientious mothers try to keep children indoors from playing outside and gaining a reputation for being ‘alley kids’. The pine groves have not existed for several decades. The area around the camp is now heavily built up. There are a few playing fields close to the camp, but the fear and insecurity that are a legacy of the civil war discourage the camp children’s use of those facilities. In any case, unlike the pine groves of the past, from the perspective of the camp’s inhabitants, the playing fields are primarily a male (Shi’a) space for boys and young men. The collapse of social ties between the camp and its environs as a consequence of urbanisation, mass population transfers, heightened sectarianism and hostility towards Palestinians, have all served to increase women’s confinement to the camp at the same time as other forces have made it possible for them to venture out for the purposes of employment and education.

Refugees’ desire to regroup along kin and village lines led to members of the same extended family and inhabitants of the same village pitching their tents near one another. This was not always the case in the initial years. Several first generation interviewees told me that due to a tent shortage sometimes as many as four families were made to share a tent and often they did not even come from the same village. Later with the establishment of UNRWA it became possible to allocate a tent for each family with larger families getting larger tents. With the formation of family and village clusters, different parts of the camp began to be referred to by the name of the family or village inhabiting them. Some scholars have viewed this as a willed act of commemoration (Peteet 2005, Schulz and Hammer 2003). However, the interviews I conducted suggest that this was not the case. As the number of family and village clusters grew, so did the need for directions. In giving directions, people began to refer to an area by the name of the family or village cluster inhabiting it.

In the early years, the orchards near the camp served as an important source of employment for men and women. With the construction of Beirut International Airport in 1954, less than a km south of the camp, and increased industrialization in the rest of the city, more employment opportunities opened up. This attracted Shi’a migrants from the poor villages of the south and the Bek’aa, as well as Palestinian refugees from the rural camps in the north and the south. The former settled in areas around the camp while the latter rented or bought houses in the camp. Some UNRWA assistance and the income brought in by steady employment—in most cases back-breaking manual labour—enabled camp inhabitants to convert their tents into small structures made out of wood or adobe and sheets of corrugated metal.

(Bourj el-Barajneh camp in the 1950s. Courtesy of UNRWA photo archives)

Childhood memories of second generation refugees are dominated by the zinc roofs of their houses. The clatter of the heavy winter rain falling on the roof or the plop of raindrops falling into the bowls and cans placed under the holes in the roof. In the summer the roof would turn the house into an oven, while the winter winds would make it fly. The construction of more durable structures and private bathrooms was prohibited by state regulations that aimed at preventing the Palestinian camp refugee presence from becoming permanent [7]. The rules were enforced by the much hated maktab al-thani, the Lebanese intelligence services, that had a checkpoint at the entrance of the camp. When those days were recounted the statement I most often heard was : “It was forbidden to even knock a nail in the wall.” An interviewee recollected that a woman who had done so was humilated for it by being made to wear trousers. Also common were recollections of the prohibition on throwing water into the street drains between sunrise and sunset which made everyday household chores such as cooking, cleaning and washing even more difficult.

In such circumstances performing everyday household chores acquired an added meaning for the camp refugee women. In addition to demonstrating their competence as wives and mothers within the community, housework provided an opportunity to resist the dehumanising effects of the maktab al-thani’s prohibitions and refute the slurs commonly heaped upon the camp refugees of being savage, filthy and disease-ridden.

It is true that I was very slow but no one cleaned better than me. My mattresses were very clean. I used to change my baby’s diapers all the time so he would remain clean. All the covers were white. When I would take my baby to be weighed he used to look like a white pigeon. I’ve never used coloured clothes. When my daughter gave birth, her son needed a blood transfusion. So we took him to A.U.H [8]. I brought a change of clothes for him. When the nurse saw his clothes she asked me, “Where are you from ?” I told her, “I’m Palestinian.” So she asked, “Where do you live ?” I told her we lived in the camp. She couldn’t believe me. She said, “From the neat and clean clothes I thought you were living in a rich place.” So I said to her, “Praise God, all his clothes are white like a pigeon.” I raised 10 children and they’ve never had to go to the hospital. It’s true that they sometimes vomited but I always kept them clean…We took very good care of our children and they listened to us even if we had 10 kids…

(Interview with a first generation refugee from Qwikat. Bourj el-Barajneh camp. April 25, 2006).

This motherly pride in properly raising children was also reflected in the emphasis many first generation mothers (and fathers) placed on their children attending the UNRWA schools and excelling at their studies. The importance they accorded to schooling was shaped in large part by their belief that their lack of ‘modern’ education [9] had enabled them to be duped by the British and the Zionists. Additionally, those refugees who had been able to make a life for themselves and their families outside of the camps had received some form of schooling in Palestine. In this sense, acquiring a modern education was not only seen as a means for economic mobility but also as a proto-nationalist imperative—a means by which what had been lost could be regained (Sayigh 1994). As early as 1949 the LRCS in conjunction with UNESCO opened tent schools in the camps for refugee children that were staffed by adult refugees who had either been teachers in Palestine or had received higher education [10]. With the establishment of UNRWA, they were moved to buildings located outside the camps.

Contrary to the popular impression that the political mobilisation of the camps was brought about by the coming of the PLO in the late sixties ; fieldwork revealed that camp inhabitants who had played an active role in the struggle against British and Zionist colonialism remained politically active in Lebanon, developing links to pan-Arab groups that were viewed as a threat by the Lebanese state to the country’s sectarian balance. In order to obstruct political mobilisation among the camp refugees, the maktab al-thani closely monitored movement in and out, as well as, between camps. In addition to the prohibition on leaving the camp between dusk and dawn, visiting another camp required a permit. Gatherings of more than a certain number were forbidden hence even funerals and weddings required prior notification and permission especially for guests from other camps. In their attempts to control the camp’s inhabitants and suppress any form of political activity, the maktab al-thani supplemented policing of their everyday lives with the use of informers, imprisonment without charge, torture, assassination, disappearance, and the arrest of family members (Sayigh 1979). However, their repressive measures merely served to further radicalise the camp’s population.

During 1968-1969, the PLO’s rise as a revolutionary force and the military successes of its guerrilla groups (fedayeen) in sharp contrast to the failure of Arab standing armies led to significant changes in the relationship between Palestinian refugee communities and the Arab states. This was reflected in the Cairo Agreement of 1969 under which the Lebanese state accepted the legitimacy of the PLO’s presence in Lebanon and the pursuit of its liberation struggle against Israel from Lebanese territory (Brynen 1990). With the suppression of PLO activities in Jordan culminating in the massacre of Black September, Lebanon became the PLO’s primary base and remained so until it was forced to withdraw in 1982. Soon after the refugee camps were released from the control of the maktab al-thani. The use of the word thaura or ‘revolution’ refers not only to this period, but also the liberation movement that was in force during this period. With the money flowing into the resistance groups from different Arab states that sought to control them, the movement established a number of bodies that functioned as the institutions of a state in exile (Brynen 1990, Rubenberg 1983). These included the Palestinian National Fund (PNF), the financial body of the movement ; the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS) that concerned itself with the provision of health care [11] ; the Palestinian Martyrs Works Society (SAMED) that was charged with providing training and employment to Palestinians, as well as supplying the refugee community with the material necessities of life at an affordable price ; and the General Union of Palestinian Workers that concerned itself with the issues Palestinians workers faced as workers in general and state-less refugees in particular.

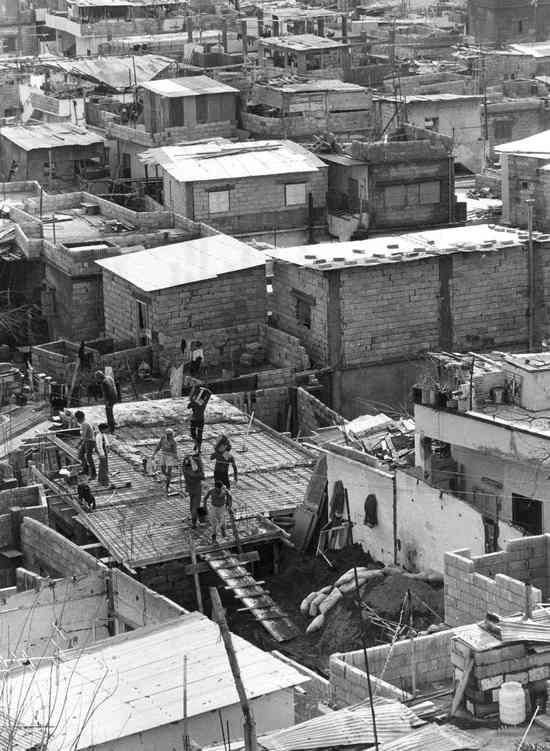

(Bourj el-Barajneh camp in the 1970s. Courtesy of UNRWA photo archives)

Most first and second generation refugees remember this period as the time when they were finally able to build. Electricity and a constant supply of piped water became available through the assistance of the thaura. Freed from the constraints of the Lebanese state, refugees were able to enlarge their dwellings, and build more durable structures from cement, along with private bathrooms. The boundaries of the camp began to extend beyond the perimeter of the area that had been officially leased to UNRWA. None of the construction was planned. Corrugated metal sheets continued to be used as roofing due to the high cost of building cement roofs ; but it was possible to replace the old adobe floors with cement and tiles that were easier to clean. For many refugees, the process was facilitated by an increase in income brought about by the thaura’s monetary injection and remittances from male family members who had travelled to Saudia Arabia and the Gulf because of the oil boom. For these families it became possible to purchase appliances such as radios, televisions, refrigerators and gas stoves that had previously been beyond their reach. A friend from the camp once told me that you could tell a lot about the way camp families thought from the size of their houses. In his words, “Those who were greedy and/or far-sighted took up as much land as they could, so their houses are bigger. Those who continued to believe that they would be returning soon didn’t care and their houses remained small.”

Since the land on which the camp is located is leased to UNRWA, in the absence of formal property ownership a notion of ownership similar to that in place in low-income Lebanese neighbourhoods in Beirut was developed by which the (male) head of the household was considered the owner of the physical structure, not the land on which it was built. This ownership was registered with the UNRWA camp director and was used as the basis to rent, buy and sell housing within the camp. With the coming of the thaura, this role also began to be performed by the newly formed Popular Committees that had representatives from all the major resistance groups, as well as a number of camp ‘elders’ Functioning as municipal bodies, the Popular Committees organised the provision of water and electricity and provided other public services such as mending and asphalting camp roads, digging wells and repairing sewage pipes. After the establishment of the PRCS, UNRWA’s inadequate health services were supplemented by the construction of a PRCS clinic in the camp that was later converted into a hospital. SAMED built a large production facility near the main entrance of the camp that in addition to producing furniture, candy and Palestinian handicrafts, served as an important source of employment for the camp’s inhabitants. In addition to the salary they were paid, SAMED workers also received monthly allowances for their spouse and each child they had, along with free medical care (Rubenberg 1983).

The construction of these new facilities and the establishment of offices, centres and clubs of the different resistance groups in the camp produced new place names. This process was similar to the one by which different parts of the camp had acquired the name of the family or village inhabiting them in that it was not conscious. The area that had previously been called Talleh for the large sandy hill where the camp’s children had played against their mothers’ injunctions now became known as the Hilal area for the PRCS clinic that was built there. The area where SAMED built its workshops became known as the Samed area, and so for the areas where the resistance groups built their offices and clubs. In many cases the same area acquired different names—the earlier village name and the later thaura name. These name-pairs coexisted side by side for a while. Some continue to do so, making getting directions and locating a particular place in the camp quite difficult for outsiders. Others acquired new names altogether or the village/family name stopped being used for them because large numbers of that family or village’s inhabitants no longer lived there. In the case of others, the village name remained even after villagers and their descendents had moved else where. This was the case for Jort el-Tarasha (Tarshiha square). It continues to be called so till today even though most inhabitants of Tarshiha moved out of the camp or emigrated/gained asylum in other countries. However, ‘willed’ naming also took place. A second generation interviewee told me that during this period her UNRWA school was named Fedaa for the fedayeen, while the one above hers was named Karameh, for the battle of Karameh that brought the fedayeen to prominence in the Middle East and abroad. These acts of naming served to commemorate, celebrate and assert the existence of the thaura and the Palestinian struggle for liberation.

Education was made a national priority and pressure was brought upon UNRWA to adopt new textbooks in its schools that taught a more nationalist history and geography of Palestine, emphasising the anti-colonial resistance to British and Zionist colonialism. Scholarships were made available for students to acquire higher education abroad, particularly in the Soviet Union and the Eastern European countries. A program developed by Fateh in Jordan for training children to be resistance fighters know as the ashbal was also implemented. Conceived as a supplement to regular schooling, it imparted basic military and physical training with lessons on Palestinian history and general political history. Various clubs, programs and activities were also established in the camp with the aim of mobilising the refugees. These often took place in the newly built centres and offices of the different resistance groups. The General Union of Palestinian Women (GUPW) ran vocational training courses and adult literacy classes at their women’s centre in the camp. They also offered lectures on parenting, maternal and infant health care. Several interviewees spoke of borrowing books from the PFLP’s lending library in the camp and joining the sports teams that were being set up by the youth clubs affiliated with the resistance groups.

The camp became a different sort of disciplinary space than the one it had been under the tyranny of the maktab al-thani. During the era of the latter, privation, fear and violence had been used with the aim of rendering the camp’s population docile. During the thaura education, health and social projects were used to politically mobilise the camp’s inhabitants to join the nationalist struggle. This is not to say that the refugees lacked political awareness, or a sense of themselves as Palestinians. The hardship and oppression they had faced since their expulsion was a keen reminder of who they were and what had brought them to Lebanon. However, the thaura sought the creation of a ‘modern’ Palestinian resistance fighter—one who had received ‘modern’ education and through it could draw his/her sense of identity from the lost homeland in its (abstract) entirety rather than through the mediation of his/her village or city of origin.

Z : At school they taught us Palestinian geography and history. Also through T.V. series. They had programs about Palestine. Also during the thaura they used to show movies about the fedayeen and about Palestine. These films talked about how the thaura started and how the fedayeen were fighting the Israelis. Also about Iz el-Deen el-Qassam, the rebel who began the thaura in Palestine [12]. All these thing we learnt through T.V. Not from our parents but from series and movies. We learnt about Palestine and how the Palestinians fought British colonialism, also Palestinian history, the ‘Sykes-Biko convention’. We studied Palestinian history at school… My sister and I were in the same training bloc. It was called the ‘Abu Abed bloc’. It was the first thing the Israelis bombed during the invasion. During training they used to ask us to hide whenever we heard belligerent planes because it was dangerous…I trained for three months. It was necessary for every child, girl, boy, man, woman and old person to be armed. Firstly, because we needed to be aware of our cause ; and secondly, because as camps we suffered a lot from the war. We suffered a lot. There was war all the time and you know that the camp is a small place so if we weren’t aware and trained how could we protect ourselves ?

(Interview with a second generation refugee from Fara in Bourj el-Barajneh April 14, 2006.)

The Lebanese civil war began in 1975, but Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon that resulted in the PLO’s withdrawal marks the end of the thaura. Israel succeeded in its aim by turning Lebanese popular support for the Palestinian resistance movement into hostility [13] through its ruthless blitzing of south Lebanon and West Beirut, and destroying the resistance movement’s organisational infrastructure of productive facilities, centres, and research institutions that had been built over the last decade. Bourj el-Barajneh camp as an important training and military base was specially targeted during the bombing. Interviewees told me that during the invasion most camp inhabitants took refuge in shelters and abandoned buildings outside the camps.

Terrifying as the invasion and its aftermath (the Sabra-Shatila massacre) were for Bourj el-Barajneh’s inhabitants, many told me that the Amal sieges (1985-1987) were far worse. The first siege lasted several weeks, the second a month, the third six months. During the invasion there had been lulls in the bombardment that had made it possible to provide medical aid to the wounded, collect and bury the dead, go outside, buy food, cook, bathe and carry out other routine tasks that maintained the semblance of everyday life. The bombardment during the sieges seemed never ending. Heavy weaponry including tanks was used against the flimsy cement walls of the camp. They were supplemented by snipers strategically placed around the camp in the rubble of high rise buildings where they had a clear shot into the houses that were on the camp’s outskirts. Electricity and water supplies were cut off. Food was only occasionally allowed in. During the six month siege people were forced to eat grass. Added to the inhabitants’ suffering was the bitter knowledge that they were being attacked by people they had considered allies in their liberation struggle, some with whom they had received military training, others who were neighbours and had also become close friends and family members through the socio-political ties that had developed between the camp and its environs especially during the thaura. The cessation of hostilities brought little relief as the Syrian army took control of the camp with the cooperation of a number of political factions in the camp. They established check points around all the major entrances to the camp. No one could enter or leaving without presenting their identification papers. For almost a year men between the ages of 15-60 were prohibited from leaving the camp unless they were members of the Syria allied factions.

The civil war was a period of repeated destruction and repeated rebuilding. Refugees received a small amount of UNRWA assistance in rebuilding their homes only after the invasion. No help was provided to deal with the much greater damage done by Amal bombardment during the sieges, and for several months after the Syrian army refused to allow building material to enter the camp.

Abu J : I rebuilt this house seven times…

Nadia : And no one helped you ?

Imm J : No. During the invasion UNRWA distributed some cement bricks and zinco according to the size of the family. They used our ration cards to determine how many family members we had…It was hellish to live in a zinco house because in the summer the zinco sheets would become fiery hot…So during the invasion our house was destroyed and we had to rebuild it.

Abu J : Three times during the invasion.

Imm J : I stood by my front door and cried and prayed to God because he protected my three sons who were with the fedayeen. Since we fled Palestine I have prayed to God to protect my family. So when I saw that my house was destroyed I said to myself it is a blessing from God that my kids survived. I don’t care about the house. The important thing is that my family members are alive…I went back to my husband because he didn’t dare come to the camp. He asked me, “How did you find the house ? Is it possible to live in it again ?” So I told him, “The house needs a lot of fixing. It reminds me of the day of the Nakba when we fled Palestine.”…So we stayed in the Bourj area for three months. Then my son’s friend gave him the key to his house and told him to stay there until the situation got better. So before the invasion was over, my son said to me, “We should go and fix our house.” Because he didn’t want his friend to think that we were going to stay there for ever. So we came here and started to fix our house. It took us about 2 months to fix it but not well…During the War of the Camps, my house was bombed again. It was destroyed. We were living in the shelter. When the situation improved we came and started fixing the house again. We spent 3 months in another house in the camp. It took a long time because we couldn’t go out of the camp to bring the materials to fix the house. The walls, the doors, the windows, everything was broken…”

(Interview with first generation refugees from Qwikat. April 2, 2006).

The events that followed the PLO’s withdrawal and the end of the thaura—the Amal sieges, followed by a bitter and bloody internecine conflict between the fighters of Fateh and the pro-Syrian groups and the latter’s collaboration with the Syrians in the arrest and torture of a large portion of the camp’s adult male population—have produced feelings of deep bitterness and cynicism towards the Palestinian political leadership. With the shift in the focus and location of Palestinian nationalist political activity to the West Bank and Gaza, the camp’s inhabitants feet they no longer have a role to play in the liberation struggle. I found it significant that very few of the first or second generation camp refugees I spoke with or interviewed, recollected the thaura nostalgically as a golden age. This was the case with even those individuals such as Abu J who had been politically involved and held positions of authority.

These days the camp presents the appearance of a tiny, dilapidated island closed in on itself. When the camp was established in 1949 many of the orchards surrounding it were owned by Christian families that lived in villages a short distance away. The construction of the Beirut International Airport in 1958 began the process of urbanisation. However, the civil war years were the period when it took place most rapidly. Christian families fled to the safety of East Beirut. Their place was taken by Muslim residents of the north-eastern low-income suburbs who had been evicted by Christian militias. They were soon joined by Shi’a refugees fleeing Israeli bombing in south Lebanon. The post-war period, saw more construction and an increase in population with former squatters who had been evicted from the city moving in since the southern suburbs offered housing they could afford. Large numbers of foreign migrant workers also began to rent housing there for the same reason. However, the camp no longer maintains the sort of social and political ties that it did with its environs in the pre-siege days.

Its boundaries are clearly demarcated by the roads that separate it from the surrounding Shi’a dominated neighbourhoods, many of which came into existence as a consequence of the massive population movements that took place during the civil war. Lebanese state prohibition against Palestinian post-war rebuilding in the areas that were not part of the origin plot of land leased to UNRWA has reduced the camp’s size. Most camp houses are two or three-storeyed cement cinderblocks. Some have as many as five. Closely packed together, they prevent sunlight and fresh air from reaching the lower stories that have to have the lights on even during the day in order to be able to see. Many houses, particularly those marking the camp’s boundary, are still pockmarked with shrapnel and shell holes. They are separated by winding alleys that are often too narrow to allow two persons to walk side by side. If you do not know your way around, it is very easy to get lost.

With the natural increase in population, high unemployment, low income levels and extremely limited space to build, families have attempted to continue the practice of post-marital patrilocal residence by building upwards if the original construction allows for it. This takes the shape of self-contained apartments built one on top of the other with a shared staircase that leads from the front door. Sometimes the staircase begins in a small shared courtyard where the motorcycle (if the family owns one) is kept. The flat rooftops serve a number of functions. They are used for storage, hanging laundry and placing satellite dishes. During summer evenings they allow for the possibility of catching a cool breeze especially if one is an adolescent girl or young woman. Though spending too much time up there un-chaperoned exposed to the gaze of male neighbours and passer-bys runs the risk of inviting gossip. Some families have created small gardens on their rooftops by planting vines, plants, shrubs, and even small trees.

The camp’s proximity to the city and low rents has created a rental housing market that is an important (and steady) source of income for many families who rent out rooms and empty apartments to other refugees from the camp, from other camps, foreign migrant workers, researchers and volunteers. Lebanese families might rent or buy housing on the very outskirts of the camp but not within it. Their relations with their Palestinian neighbours are not always cordial. In discussing the presence of non-Palestinians in Bourj el-Barajneh camp, it cannot be emphasised enough that unlike Shatila camp, their presence is not considered a significant one. Whether this has to do with the difference in the actual numbers of non-Palestinians living in the two camps, their nationality [14], or the size of the camps is difficult to determine. In Bourj el-Barajneh, the foreign migrant workers keep to themselves. They consist for the most part of single-sex groups of unskilled or domestic workers sharing a room or an apartment together. They include Syrians, Bangladeshis, Sri Lankans, Sudanese and Egyptians. The camp’s inhabitants view the Syrians with suspicion and hostility that stems from their bitter experience of the Syrian army’s tyranny and brutality. However, there have not been any incidents of violence against them perhaps because they are suspected of being informers. The camp inhabitants’ view the Bangladeshis, Sri-Lankans and Sudanese with the same racist contempt that the latter encounter among the Lebanese. Like the Lebanese, they too use the word Srilankiye to refer to a maid instead of the Arabic word khadima. I heard a number of women refer to themselves as ‘Srilankiye’ in order to express how over-worked, ill-treated and disrespected their husbands, children and/or families made them feel.

Unemployment and underemployment in the camp, particularly among men, are very high. Most men work as contractual labour in the construction industry. A number of women work for the various NGOs providing social and educational services in the camp. Many households rely on remittances from family members working abroad to remain afloat. The withdrawal of the PLO, and the destruction of SAMED by Israeli bombing and then Amal bombardment drastically reduced employment opportunities and income levels. The state of the Lebanese economy ; the post Gulf war closing of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia to Palestinian migrant labour after Yasser Arafat’s expression of support for Sadam Hussein ; Qaddafi’s expulsion of a large number of Palestinians following the Oslo Accords ; the decline in the Gulf’s states’ need for foreign labour ; and the increased tightening of borders in order to deter terrorism and economic migration have exacerbated the situation.

Globalized media sources are easily available through inexpensive, informal satellite connections and the internet cafes that have proliferated in the camp over the last five years. Inflaming desire for the consumption driven lifestyles they project, they constantly remind the younger generations of what they lack, heightening their sense of feeling ‘stuck’ or ‘trapped’ as life passes them by. This enormous sense of frustration is projected on to the space of the camp and the fact of being a Palestinian camp refugee in Lebanon.

Postscript :

March 26, 2006

I inadvertently provoke a fight between L and her daughter, G, today when I bring up the subject of G travelling to Italy. A mutual friend and I talked about trying to set this up for G as she’s been offered room and board by one of L’s many ajanib [15] friends with her mother who lives in Italy. We didn’t know what exactly the offer entailed so we made a plan to sit down with L, find out more and try and convince her to follow it through so that G can finally take advantage of an opportunity she will never have again. According to G and Lara, G has been offered vacations and study abroad opportunities by various ajanib friends of her mother. There’s always been a lot of talk but in the end it always comes to nothing. While talking to L I discover the following :

_She evokes religion to end a discussion. To provide a justification for constraints she feels are unjust and she has no control over ; i.e. their lack of money and the difficult of being able to travel as a Palestinian.

_L will not take up her friends’ offers because in her words it’s a question of boundaries. She doesn’t want to cross her friends’ boundaries.

L : Even if they offer her free room and board, won’t she have other expenses ? Can I accept someone else paying for her upbringing and her education ? You love us. But can you bring her up, care for her and protect her the way I, her mother, protect and care for her ? We all have dreams. I had my dreams when I was young. Didn’t I want to travel abroad, to get away from this shit camp and this shit life ! But we have to live in reality. Do you want me to get her hopes up and then it doesn’t happen ? Imagine how she’d feel then.

After this conversation I feel quite depressed. G and I watch a Hilary Duff remake of Cinderella. We both cry at the bit when the evil step-mother gives her a fake letter of rejection from Princeton so she’ll stay and work in the diner. But I suspect that the bit about getting her humiliated in front of the whole school and the boy she’s in love with—including the boy not standing up for, makes G sadder.

Nadia Latif

Doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology

at Columbia University.

Her dissertation examines the relationship

between kinship, belonging to place and the articulation of national

identity in the context of a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon.

Bibliography

Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined Communities. London : Verso.

Brynen, R. 1990. Sanctuary and Survival

The PLO in Lebanon. Boulder : Westview.

Diken, B., and B. Laustsen. 2005. The Culture of Exception

Sociology Facing the camp. London : Routledge.

Fawaz, M., and I. Peillen. 2003. The case of Beirut, Lebanon.

Foucault, M. 1990. The History of Sexuality : An Introduction. New York : Vintage.

—. 1995. Discipline and Punish. New York : Vintage.

Gorokhoff, P. 1984. "Création et évolution d’un camp palestinien de la banlieue sud

de Beyrouth, Bourj el-barajneh," in Politiques urbaines dans le monde arabe, pp. 313-330. Lyon : Maison de l’Orient Méditerranéen.

Hagopian, E. C. Editor. 1985. Amal and the Palestinians :

Understanding the battle of the camps. Arab World Issues. Belmont, MA.

Halbwachs, M. 1992. On Collective Memory. The Heritage of Sociology. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

Hirschon, R. 1989. Heirs of the Greek Catastrophe

The Social Life of Asia Minor Refugees in Piraeus. New York : Berghahn Books.

Hyndman, J. 2000. Managing Displacement

Refugees and the Politics of Humanitarianism. Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press.

Lefebvre, H. 1984. The Production of Space. Oxford : Blackwell.

Malkki, L. 1995a. Purity and Exile :

Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology Among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

—. 1995b. Refugees and Exile : From Refugee Studies to the National Order of Things. Annual Review of Anthropology 24:495-523.

—. 1996. "National Geographic : The Rooting of Peoples and the Territorialization of National Identity Among Scholars and Refugees," in Becoming National. Edited by G. Eley and R. G. Suny, pp. 434-453. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Perera. 2002. What is a Camp ? Borderphobias–the Politics of Insecurity Post-9/11. borderlands 1.

Peteet, J. M. 2005. Words As Interventions : Naming in the Palestine-Israeli Conflict. Third World Quarterly 26:153-172.

Picard, E. 2002. Lebanon : A Shattered Country. New York : Holmes and Meier.

Rubenberg, C. 1983. The Civilian Infrastructure of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation :

An Analysis of the PLO in Lebanon Until June 1982. Journal of Palestine Studies 12:54-78.

Sayigh, R. 1979. Palestinians : From Peasants to Revolutionaries. London : Zed Books.

—. 1994. Too Many Enemies

The Palestinian Experience in Lebanon. London : Zed Books.

Schulz, H. L., and J. Hammer. 2003. The Palestinian Diaspora

Formation and Politics of Homeland. London : Routledge.

NOTES

[1] Medical Aid for Palestinians United Kingdom. May 29, 2007.

[2] UNRWA. May 23, 2007.

[3] League of Red Cross Societies report to the United Nations Relief to Palestine Refugees. May 1949. IFRC archives. LRCS. Box 19724

[4] Anthropologist, Rosemary Sayigh, provides a similar account of the establishment of Shatila camp in her ethnography, Too Many Enemies : The Palestinian Experience in Lebanon.

[5] A large Lebanese vocational training school opposite the eastern boundary of the camp.

[6] The population figures are taken from the UNRWA website, while the size of the camp is a commonly used estimate based on the size of the land originally allocated for the camp.

[7] A study conducted on the camp in 1980 stated that one of the official reasons given for the prohibition on constructing private bathrooms was that the refugees had no sense of hygiene (Abu-‘Ala, Hussein 1980).

[8] The American University Hospital. Affiliated with the American University of Beirut, it is considered to be one of the best hospitals in the country.

[9] Most villages in pre-1948 Palestine had had a kuttab, where boys learned rudimentary literacy through reciting the Quran.

[10] League of Red Cross Societies Report of the Relief Operation in Behalf of the Palestine Refugees. 1949-1950.

[11] The PRCS does not differentiate between Palestinians and non-Palestinians in the provision of its low-cost services and till today is one of the main sources of health care for low-income Lebanese and foreign nationals working in Lebanon.

[12] The rebellion against the British occupation and against land sales to Zionists in 1936-1938.

[13] Though it must be noted that the resistance groups achieved this on their own too through the arrogance with which the fighters often treated the Lebanese—particularly in the south—and the disregard they showed for risking the latter’s lives, homes and means of livelihood.

[14] Syrians and Lebanese Shi’a form a much larger proportion of non-Palestinians in Shatila than in Bourj.

[15] Arabic for “foreigner” ; more often used for a Westerner than for someone from a non-Western country.

Fil des publications

Fil des publications

retour au sommaire

retour au sommaire